Bitcoin crash course

Aug 1 2018I’ve just moved to London, and been working on LMAX Digital and as a result been given a bit of a crash course on how exactly Bitcoin (and other cryptocurrency) transactions actually work. I think there’s a near zero chance I’m going to remember it as I’ve moved on to another area of work, so I figured I’d better write it all down before I forget it all.

There’s quite a few concepts associated with the bitcoin blockchain, but probably the most important one, and one of the few that exists as a concrete object is the transaction. This is what actually goes into any given block on a blockchain.

So let’s talk a little about the structure of the actual payments or transactions. There’s some header information, but mostly they consist of inputs and outputs. The inputs are the unspent outputs in a previous transaction that you have the ability to spend, and the outputs are the payments that you want to send to other addresses. Of course it’s a little more complicated than that, since we have to have some verification - you have to form a transaction that proves you can actually spend the inputs, and create some sort of condition that needs to be met for the recipient to spend your outputs.

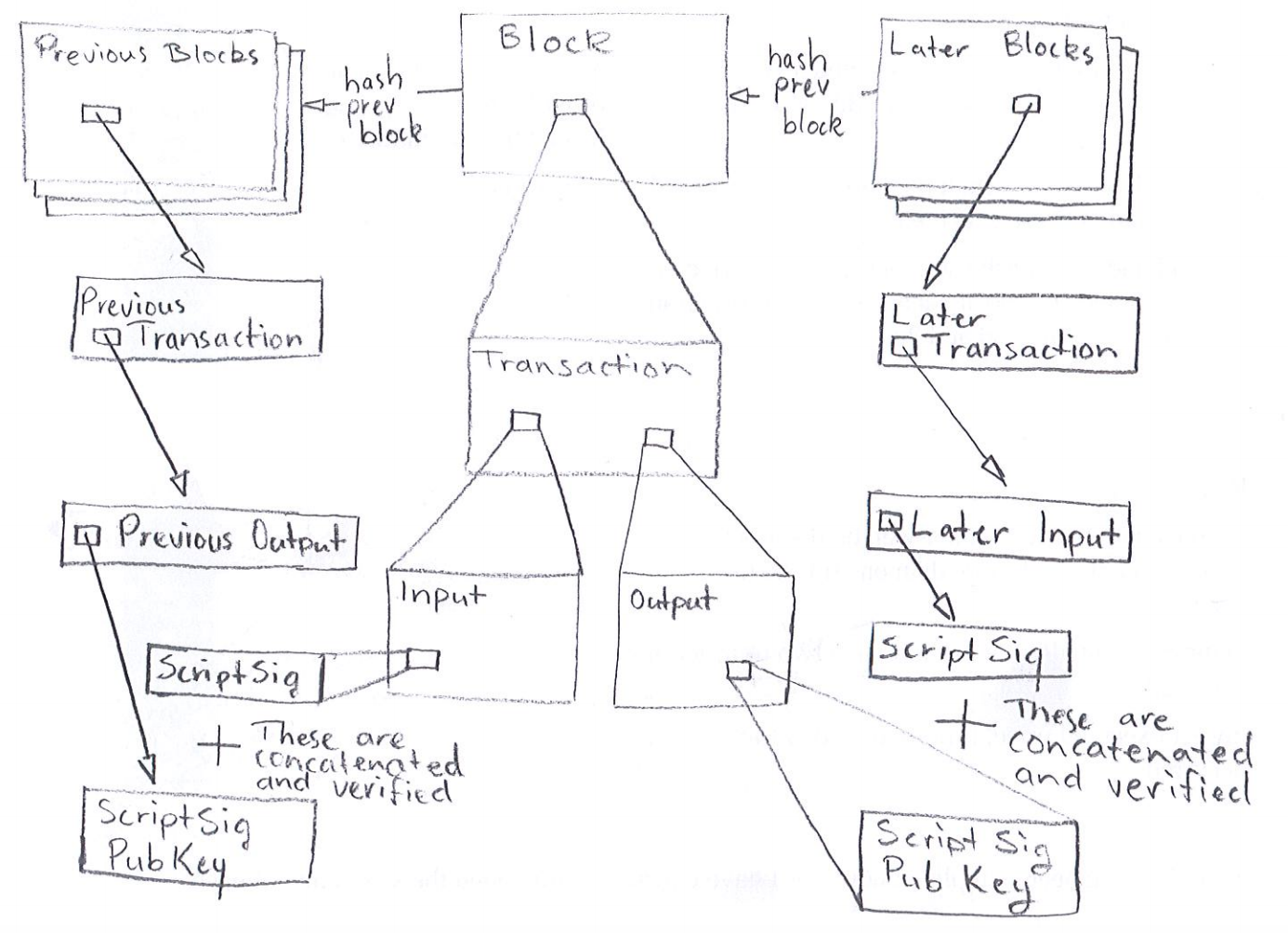

This is done by building up a script from the inputs and outputs of transactions. The script is run by all the nodes participating in the bitcoin blockchain to verify that the inputs are allowed to consume the outputs from older transactions they refer to. The structure is fairly recursive, and probably best described in pictures, rather than words:

There are other parts I’ve omitted from this diagram: the outputs also contain amounts, and the block itself has a header with various information including a value that whoever is mining the block can tweak to try and produce the desired hash. There’s many other parts that are even more ancillary to the process, if you’re interested refer to the bitcoin wiki.

It’s easiest if we consider the output first, as these form the input to the next transaction. Each output specifies a

script, written in a forth like language. This specifies what scriptSig is needed to unlock the output and

spend it. When it comes time to spend that output, we prepend the scriptSig that’s provided with the input, and

check that the script leaves true on top of the stack.

Let’s work through an example of that. The most common script is Pay-to-PubkeyHash which looks something like:

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG. <pubKeyHash> is a placeholder for the hash of an actual

public key, provided by whoever wants to receive the payment. This is often what’s referred to as an address.

The corresponding scriptSig that’s used to spend this transaction will look like: <sig> <pubKey>. The reason for

this is that public keys can be relatively widely shared or unsecured, so we include a signature generated from the

private key which can be verified by using the corresponding public key. So we join the two together and get:

<sig> <pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

So anything that isn’t an operation get’s copied straight onto the stack, so the first thing that happens is the

<sig> and <pubKey> are pushed onto the stack:

Stack:

<sig> <pubkey>

Remaining Script:

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

OP_DUP copies whatever’s on the top of stack and pushes it onto the stack, yielding:

Stack:

<sig> <pubkey> <pubkey>

Remaining Script:

OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

OP_HASH160 hashes the value on the top of the stack, then pushes it back onto the stack, giving us:

Stack:

<sig> <pubkey> <pubKeyHash>

Remaining Script:

<pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIG

The pubKeyHash from the script then gets pushed onto the stack, and we then compare it to the hash we generated

in the previous step. This is the first point at which we actually check the input is allowed to be spent, by

verifying that the pubkey corresponds to the hash in the script. If this step fails, the transaction will get

rejected by miners and not included in a block. Assuming this succeeds, we then move on to the final step:

Stack:

<sig> <pubkey>

Remaining Script:

OP_CHECKSIG

OP_CHECKSIG does what it says on the can, checking the signature on the stack was produced using the private key

corresponding to the public key on the stack, and that the signature is for the contents of the entire transaction.

This leaves either true or false on the stack, which indicates if the transaction is valid or not.

At this point the transaction can be broadcast to the blockchain, where miners will run the same set of checks before deciding if they want to include it in the block they’re mining or not. Their choice is mostly based on how many bitcoins you’re willing to give them: during the process of forming a transaction you should leave an amount from your inputs that isn’t allocated to an output for the miner to claim, to incentivize them to pick your transaction to be included in the block.

As each block is of a fixed size (1mb at the time of writing) miners will want to pack the block with the transactions offering the highest payout to them. For this reason transaction fees are often measured in Satoshis per byte (a Satoshi is the smallest useable increment of a bitcoin: one hundred millionth of a bitcoin).

What I think is most interesting about this is what we left out: we didn’t talk about wallets or addresses, since they’re abstractions we’ve built on top of transactions. A wallet is, at a bare minimum, the keys required to produce the signatures for a given output. Often we want other features like knowing the balance we have available (that’s the sum of all the unspent transactions we have the ability to produce signatures for).

Similarly, an address is really just a output script that you know you can fulfill the requirements for. Typically

you’ll only supply the pubKeyHash in the script we worked through above, but of course if you’re using a multisig

wallet or something else more exotic, you can ask whoever is paying you to use a more complex script.

This about sums up what I think are the essential elements of the bitcoin blockchain, which is to say, transactions and their constituent parts. Of those parts the most complex and crucial to the operation of the bitcoin payment infrastructure is the script mechanism, used to verify that you’re actually allowed to spend any coins sent your way. If you’ve got any questions or got corrections, message me on twitter.