Reducible Systems

Feb 6 2019A while ago I had a minor revelation about why I’m ok with working in the LMAX codebase. I’ve got a pretty strong interest in functional programming by way of Clojure, so you’d think working in a system where pervasive mutation is the rule rather than the exception would slowly drive me nuts.

I think there’s a few reasons I’ve retained my sanity, but the most important one is the way the system is designed it’s easy to keep a mental model of, and that model isn’t often broken. Why is that the case, though?

LMAX’s production system

In order to explain I’m first going to have to give you a bit of background. The production exchanges at LMAX have around 70 services at last count. There’s a few major categories however, and we’re only going to concern ourselves with what we call the “core” services: the Execution Venue (EV), also known in industry parlance as a Multilateral Trading Facility or MTF. And it gets called “the exchange” relatively often as well. The other service that’s similarly designed is the Execution Management Service (EMS), also known as “The Broker”. Again, the wider industry would probably refer to it as an Order Management System

What is it that makes these services different? Our core services do most of the heavy lifting in our system. They’re where most of the “business logic” actually resides so we have high speed and resiliency requirements for them. These are largely met by running the core services in hot-hot pairs, which in turn means we need the services to be deterministic.

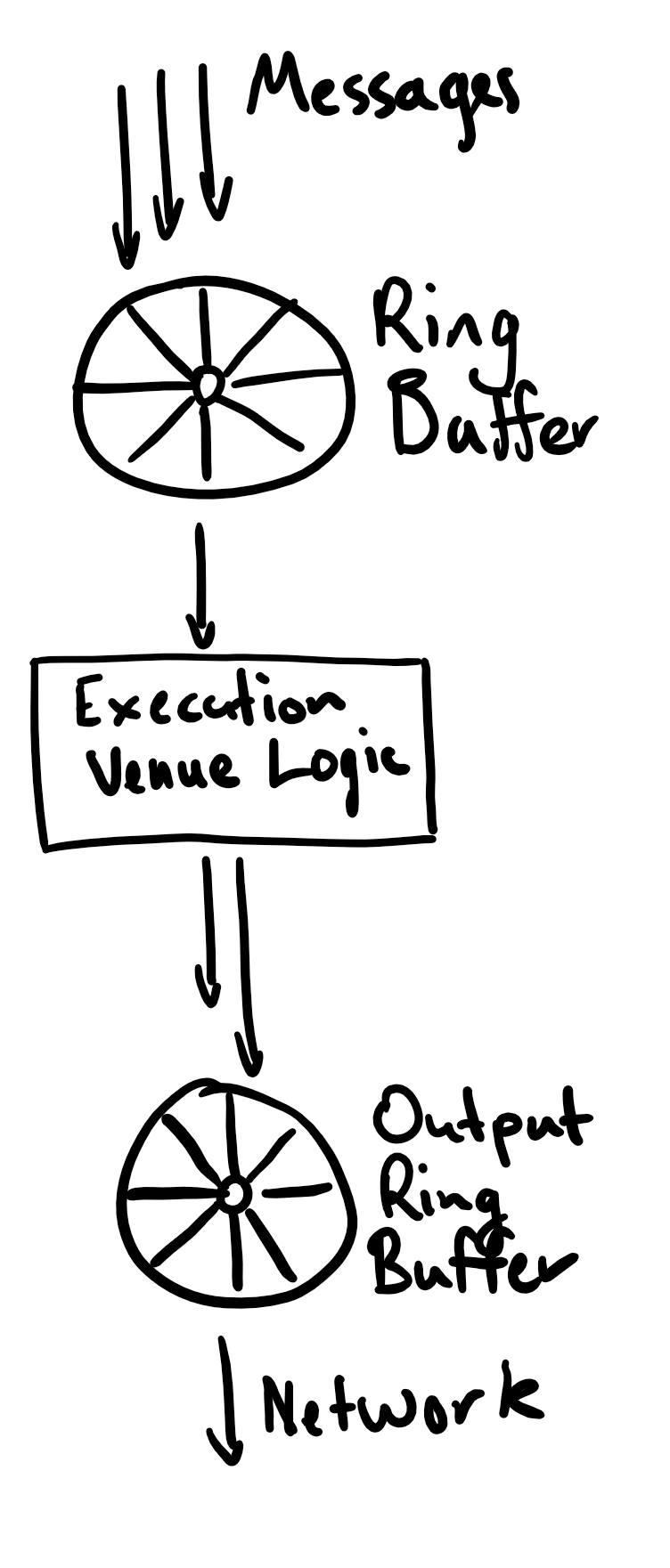

So our requirements have led us down a path that results in a design something like this:

What’s important to note about this is that the ordered, replicable journal that is the disruptor in front of the service is what enables so many of the desirable characteristics of the system.

As I mentioned, mutability is fairly pervasive in these systems. Especially in the EMS, there’s a lot of account level state that can change over the lifecycle of an order. You’d think this would be a cause for concern for me, and it was initially, but I don’t really worry about it now.

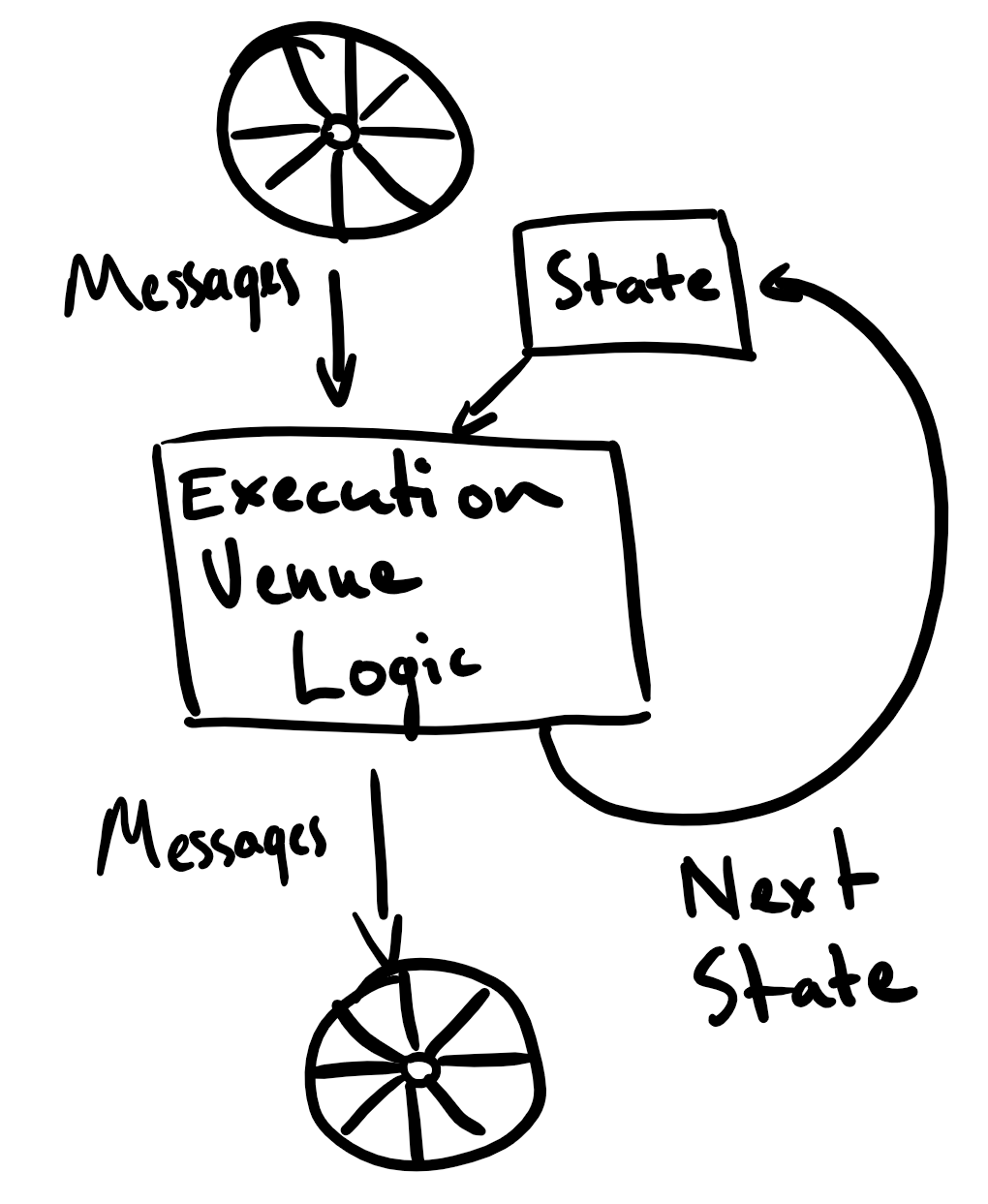

Why? Well, let me redraw that diagram above.

Basically, I think our core services are modellable as big reduce style

operations:

class Ev {

public Pair<State, Collection<Message>> processEvMessage(

State s,

Message m) {

//... do some actual work, produce messages etc ...

}

}

This isn’t strictly speaking a reduce operation since the accumulator (state)

isn’t the only result of the function, but we could just as easily stuff the

output messages in there.

Anyway, that was the revelation that I had. Our system can be viewed as a giant

reduce operation over a stream of messages. Not only that, but I think this

idea generalizes a bit.

The Duality of Message Passing

I think this idea of a system based around message passing being “trivially” convertible to a reducer can tell us a lot about the gaps in the message passing toolkit.

We have a wide variety of primitives for composing functions that operate on values together, but far fewer corresponding way of composing objects or actors in systems that operate on messages.

For instance the problem of fan-out is trivially handled in Clojure:

(->> messages

(map (juxt do-thing-one do-thing-two))

(reduce combine-thing-results))

(Juxt creates a function that calls the provided functions, returning their results in a collection)

When we have to do this in the LMAX codebase it invariably involves a new class

called SomethingFanOut. Admittedly this may be due to our choice of Java,

which is somewhat notorious for the amount of boilerplate you’re required to lay

at it’s altar.

Looking at the advantages that message passing has, I think the primary one is to allow us to encapsulate things we’d regard as distasteful or downright wrong and still present a clean interface to the outside world.

This allows us to take up more complexity into our code than a reducer function does, especially since within any given method we can spread our state out still further across more sub-components, while a reduce function needs to hold all of it’s state inside the accumulator value.

Again, flipping it over to the message passing side, I think this tells us that we need to tightly control any possible changes to our state. Anything that isn’t fed through a serialized message stream is a cause for concern, since we could find ourselves with state that isn’t reproducible.

This rules out querying a database directly from any service that we want to maintain this reducibility around, and indeed this is a constraint we enforce in the LMAX code base - all database interactions have to be routed via a “general” service that pushes the response back to us over the message bus. The re-frame docs also strongly advise us to to avoid any impurity in our application and to instead push that to the edges of the system.

I think there’s also lots of benefits to be gained from this duality, along with quite a few we’ve already realised. Let’s have a look at what this effort has yielded at LMAX.

The usefulness of reducefulness

There’s many occasions where we’ve wired up a core service to a journal from production and replayed all the messages from it, so we can examine the state of the application as a particular message or series of messages pass through it.

It’s also useful to replay production traffic through a system for performance testing, allowing us to run production traffic with assertions enabled, etc. The reason we have these journals in the first instance is for our recovery and failover strategy. We want to ensure we can bring our system back up to the same state it was in if anything goes wrong. That we can ship them around and use them for many other purposes is a great side effect of this choice.

If there’s one thing you take away from this post, if you can record an executable journal of your system’s state, I would try to do so. Being able to replay a bug repeatedly until you’re sure what’s happened, fix it, and then watch it not happen is one of the best workflows I’ve experienced.

The accumulative approach also suggests another way to design our system, one that I’ve seen before, in fact. For a while the “one big atom” model has been relatively popular in the Clojurescript ecosystem - several popular libraries such as re-frame and om both use this pattern for state management.

I think there could be several benefits to this pattern for LMAX’s core services. It could allow us to shed a lot of the persistence services we’ve written, by using our secondary and tertiary instances as read only slaves. That would also eliminate a ton of the boilerplate we write to persist configuration changes to a database and generally ensure the database and core services remain in a consistent state.

It would also allow us to roll back a failed transaction, mark a message as dead and continue operating - something we cannot presently do without manual intervention and the risk of state corruption in the core services. We probably won’t be able to do this - the performance impact would probably be too high. This should not dissuade you from considering it, many environments do not have our performance constraints.

Finally it would allow us to more easily snapshot the state of the core services, since we’d already have a handle on the root of the state tree. Having easily snapshottable event streams is an advantage in other situations as well. For many of our analytics workload we work of a stream of orders, and want to coalesce these into a image of the state of the order book at a given moment. Having systems where this is baked into the design would make our lives a lot easier in this case.

Other reducible systems

I don’t think LMAX is the only place where these kinds of systems are in use. In fact, I’ve got a much stronger claim: I think almost every system relies on something like our core applications in order to actually make their system understandable.

Most multitier-architecture web applications involve some sort of concurrency, either involving threads or some other sort of way of getting more work out of the multiple cores available in your server.

The problem comes when you’re trying to get something involving state done. The interaction between concurrency and state is an area where a lot of things can go very wrong. Having to deal with it in your application is something we generally try to avoid, and instead make them stateless if possible. This means we push all of that mess down to the workhorses of web applications: databases.

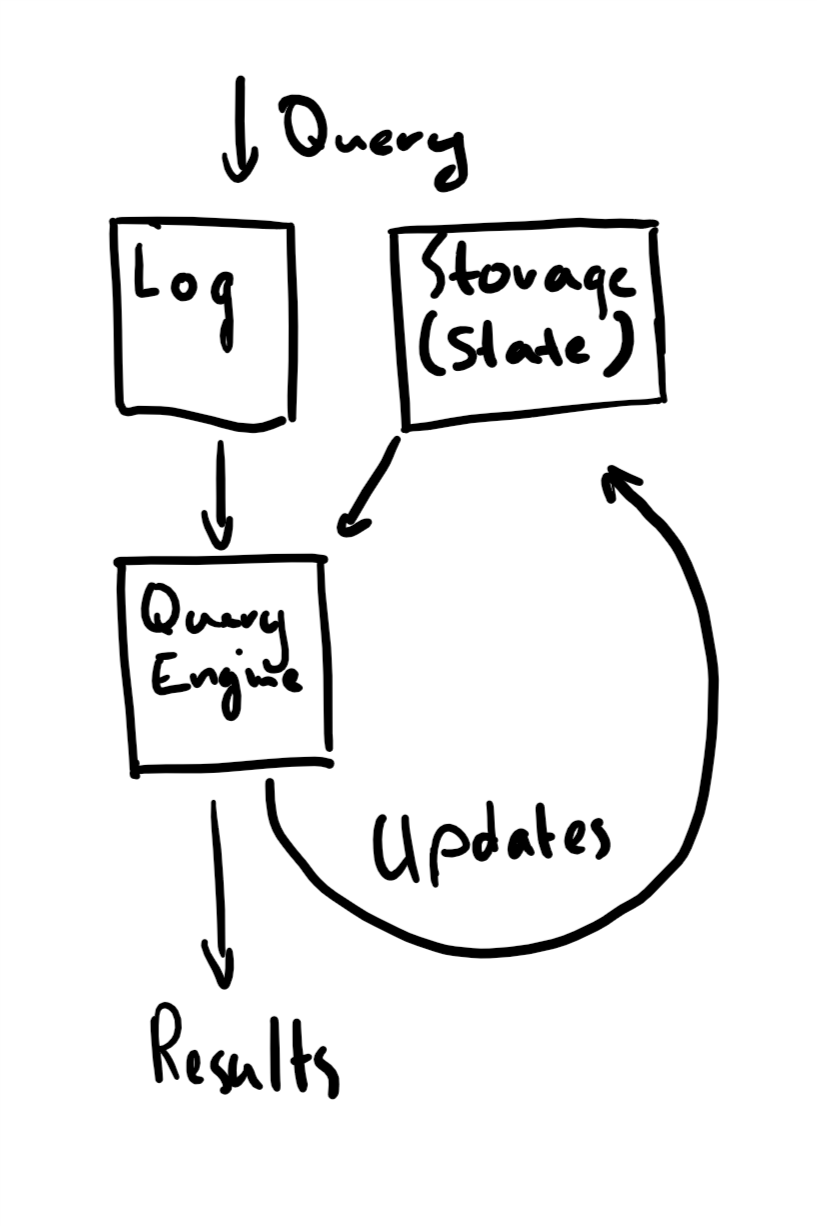

The key thing is that every relational database uses a query log in order to ensure queries are executed in a well known order. There’s a lot of optimizations in most databases to get them to actually execute concurrently, but as application programmers, we can assume that serializability holds.

Databases also, of course, serve as big repositories of application state. Here’s a (rough!) sketch of the design - contrast it to the “EV” diagram above.

Databases offer us the same constraints as LMAX’s core applications. There’s a very clear sequence of events. We can get a very good idea of the application’s state (which we’ve outsourced to the database) and what allowed transitions and mutations could, should and did actually occur. Without this I think it gets much, much harder for us to reason about the way our programs really operate, especially when something goes wrong. It becomes much easier to become trapped in quagmires of FUD when trying to add new features to your codebase.

There are other examples in other domains: React and the tools built on top of it ( flux and the aforementioned re-frame and om) have dramatically reduced the cognitive burden of working on large front end applications, by using the same idea of serialized messages altering state. (and then deriving data from it)

The thing that these systems make more clear is the usefulness of having your state in one place and being able to easily query it. I think that’s a thing that many systems built around message passing get wrong. You don’t need to protect your application state from your other the outside world if you control the ways they’re allowed to update it.

Conclusions

While maintaining the invariants needed to build a reducible system does involve quite a bit of hard work, in our case we’ve found the payoff to be worth it. Both in terms of performance and productivity it’s a terrific aid once your system has grown to a reasonable size. Anecdotally, the productivity boost I felt when moving to Clojure is roughly the same amount as I found when I started working with and in LMAX’s codebase.

Unfortunately I’m not sure how broadly applicable this is. I know it works at LMAX, but I think generalizing “reducible messaging” to other environments (without doing all the heavy lifting we do at LMAX! Our process might be overkill for many other lines of business) needs something along the lines of “re-frame for the backend” which I don’t think is a small amount of work!

All that aside, I think there’s some interesting ideas we can gather from studying the differences between these kinds of systems that should be the same, but aren’t quite.

If you’ve got any thoughts or feedback, I’d love to hear from you. The best way to reach me is on twitter - dm’s are open.

Big thanks to my colleague James Byatt, for seeding and helping me to refine this post, and also to to Nick Palmer for reviewing it.